Is Stalling a Major or Minor Fault?

Driving test nerves can be a big problem for many test candidates. All sorts of mistakes can occur during a driving test, all of which rarely occur during driving lessons. One of these mistakes can be stalling the car. But the questions is; is stalling a serious or major fault, or is stalling simply a minor fault?

Driving test faults are categorised as:

- Dangerous fault

- Serious fault

- Minor fault

A dangerous fault is where a mistake is made that puts you, the examiner and/or other road users in danger. A serious fault isn’t dangerous, but has the potential to be. Either a serious or dangerous fault is an immediate test failure.

Minor faults are actually just called driving faults now, but many still refer to them as ‘minor’ faults simply due to the word being more descriptive. A driving fault is not dangerous, but repeatedly making the same mistake can result in a serious fault. This is because repeatedly stalling demonstrates a lack of control.

Truth is, stalling on the driving test can be either a dangerous, serious or minor fault because it all depends on where you stall, how many times you stall the car and how you recover after stalling. To give you a better idea of how stalling might effect the outcome of your driving test, let’s look at some examples so that you understand how you might be marked for stalling during a driving test.

Dangerous Faults Due to Stalling

A dangerous fault will typically occur due to another driver having to take remedial action due to a mistake made by the test candidate. Stalling during a driving test that results in a dangerous fault may involve a scenario within the following situations:

Stalling When Moving off in Traffic

While waiting in a queue of traffic, the test candidate begins to move off and stalls. The vehicle behind the test candidate brakes to avoid a collision.

Stalling in the Middle of a Controlled Junction

While waiting to turn right at a set of traffic lights, the test candidate stalls. Traffic begins to flow from other directions before the test candidate has had time to recover and exit the junction.

Making a Right Turn / Crossing the Path of Oncoming Vehicles

The test candidate is making a right turn into a minor road, begins to move off and stalls, causing approaching traffic to stop or swerve around the stalled vehicle.

Stalling When already Crossed the Junction Lines

The test candidate moves off at a junction or roundabout and stalls over to give way line, causing other drivers to alter their path around the test vehicle.

The scenarios above are examples of what may result in a dangerous fault due to stalling. There are other possible examples that could be given, but those give you an idea of what might result in a dangerous fault.

Serious Faults Due to Stalling

A serious fault may be received from the examiner due to similar scenarios as those that result in a dangerous fault. The difference being; rather than your actions being dangerous and directly impacting other road users, causing them to change speed or direction, your actions are a potential risk to to other road users rather than an actual risk. Stalling during a driving test that results in a serious fault may involve a scenario within the following situations:

Stalling at a Junction / Right Turn

- Taking too long to recover from the stall and causing a delay to other road users.

- Test candidate’s vehicle moves off and stalls in an area that’s potentially dangerous to other road users.

- The vehicle stalls, test candidate attempts to start engine whilst in gear (clutch not depressed, no handbrake). Car jerks forward into new road.

Stalling When Moving Off Uphill

The test candidate is asked to park up on the left on an uphill slope. When they attempt to move off, their car stalls and begins to roll backwards. They fail to secure the vehicle from rolling backwards in a timely manner.

Stalling Too Many Times

There’s no specific amount of times that the driving test examiner considers ‘acceptable’, but roughly speaking, if you stall three or more times and all of the stalls are marked as a driving fault (minor), there’s a good chance the culmination of faults may result in a serious.

However, stalling under different circumstances can reduce your chances of failing. For example, if you stall when setting off at the test centre, stall during a manoeuvre and stall when attempting to move off from the side of the road, there’ll be less chance of failing than if all stalls were the same circumstances.

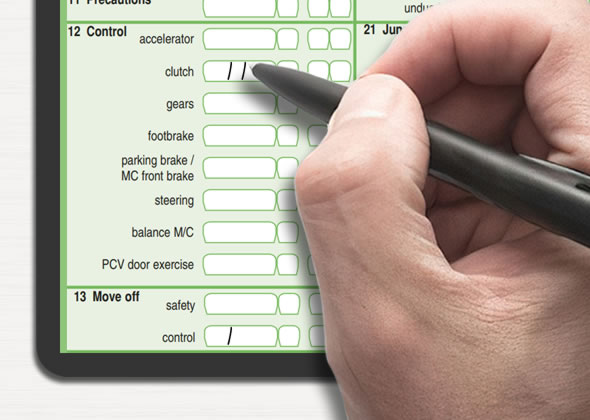

Stalling and the Driving Test Report Sheet

Stalling the car is considered as a lack of control. On the driving test report sheet, stalling is marked either under the category: 12. Control / clutch, or under the category: 13. Move off / control.

Driving Faults (Minors) Due to Stalling

Finally, we have driving faults, or ‘minors’ as they were once referred to. You may receive a driving fault from the examiner when stalling in an area that isn’t potentially dangerous or actually dangerous. Stalling during a driving test that results in a non-serious or non-dangerous fault may involve a scenario within the following situations:

Moving Off From the Side of the Road

When asked to move off from the side of the road, the test candidate stalls the car. No other road users are affected by the test candidates actions.

Stalling in Traffic

The test candidate stalls the vehicle in a non-dangerous location when attempting to move off in traffic. Recovers from the stall quickly, other road users only have a short wait.

How to Recover From a Stall

If you stall the car during a driving test, your priority is to get the car started and moving off while maintaining safety and control at all times. If you stall, it is not mandatory that you put the handbrake on and the gear lever into neutral before attempting to restart the engine. Doing so unnecessarily, will just add delay to the process. There are various methods for recovering from a stall depending on your circumstances and how you operate the car.

If you recover from a stall quickly, by causing little delay to those behind you, whilst maintaining safety and control throughout, you may only receive a driving fault (minor) or no recorded fault at all.

Method 1

If you’re able to, this is the quickest method to recover from a stall. It does however depend on your capabilities and circumstances.

- Firmly press the footbrake

- Leave the car in 1st gear

- Depress the clutch

- Start the engine

- Off the footbrake and set the gas

- Raise the clutch (slower at the bite point)

- Car begins to move off

Method 2

Use this method if you stall on a slope (avoid rolling) or if you always need to find the clutch bite point before moving off.

- Firmly press the footbrake

- Apply the handbrake

- Leave the car in 1st gear

- Depress the clutch

- Start the engine

- Off the footbrake and set the gas

- Slowly raise the clutch to the bite point

- Release handbrake

- Car begins to move off

To save time, it’s best to leave the car in 1st gear rather than going into neutral before starting the engine. Always ensure that you fully depress the clutch before attempting to start the engine if the car’s in gear. Failure to do so may cause the car to lurch forwards, likely resulting in a serious or dangerous fault. *For some cars, it’s a safety requirement that the clutch is depressed before starting the engine, else the engine will not start.